I realize that some folks are concerned about the music they will hear when they attend a performance of Nixon in China. People worry that it will be “ugly;” that they won’t be able to discern a melodic line; that it will be “too minimalist.” I appreciate those concerns and understand them, because for a time in the last century it seemed that all “new music” eschewed tonality, melody, and whatever it is that makes us enjoy listening. That is no longer the case, and is certainly not the case in John Adams’s Nixon in China, composed in 1987.

Adams is often called a minimalist composer, but he is much more than that – and his musical style is more complex and interesting than what we consider to be minimalist. His minimalism is influenced by romanticism as well as the sounds of North American music. He is challenging and accessible, driving and soaring. But acclaimed music writer Alex Ross, in his book The Rest is Noise, says it much better:

[Adams’ music is] a stream of familiar sounds arranged in unfamiliar ways….It is present-tense American romanticism…plugging into minimalist processes, swiping sounds from jazz and rock, browsing the files of postwar innovation.

Thomas May, who has written an excellent book on Adams, The John Adams Reader (Amadeus Press), will be in Vancouver on March 2 for our Opera Speaks series. He and conductor John DeMain will have lots of enlightening things to say about Adams’s music. I want to quote a paragraph in his book, citing the liner notes from the Nonesuch release of the opera recording:

Adams believes in the rich possibilities of his chosen musical language. He likes to quote the assertion by the composer Fred Lerdahl that "the best music utilizes the full potential of our cognitive resources." (Lerdahl cites Indian raga, Japanese koto, jazz, and most Western art music as good examples, Balinese gamelan and rock as musics that fail in this respect.)

More, Adams, who really is one of those composers who love music, not just their own music, and whose knowledge is encyclopedic, believes in his harmonic style as a human necessity and is willing to risk taking the controversial position of maintaining that our response to tonal harmony is not so much cultural as genetic.

"Something tremendously powerful was lost when composers moved away from tonal harmony and regular pulses," he has said. "Among other things the audience was lost."

He invokes Walt Whitman: "He has nobility, he was a social radical, and he wrote plain English." And Dickens, one of his "great inspirations": "He had a huge audience, he had profound compassion, he spoke on social issues – and he wrote for money." So did Handel and Verdi, who brought their musical ideals into harmony with the assumption that it is pointless not to please your audience.

I think this quote will help dispel any concerns regarding John Adams’s desire to compose accessible music enjoyable to all of us!

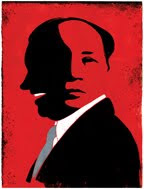

I want to choose one example in the opera for a bit more exploration. In Act II’s stunning and pivotal opera/ballet The Red Detachment of Women, an extremely ideological piece devised by Jiang Qing (Madame Mao), the stunningly naive Nixons are horrified by what is depicted on the ballet stage and its blunt presentation of political good and evil. In some ways this is the centrepiece of the opera, and vividly depicts for us the confusion, stress, and emotional exhaustion - and perhaps lack of emotional preparation - of the American visitors. Adams’s music here is amazing. Again, Alex Ross:

The music mixes secondhand American pop with secondhand Strauss and Wagner, at one point mashing the Jochanaan theme from Salome into “Wotan’s Farewell” from Die Walkure. It’s a half-charming, half-repulsive simulacrum of totalitarian kitsch.

When I first heard this music I was mesmerized… and when I first heard the particular bars “mashing” Jochanaan and Wotan, I nearly fell off my chair.

~ James W. Wright, General Director

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 Response to "The Music of John Adams"